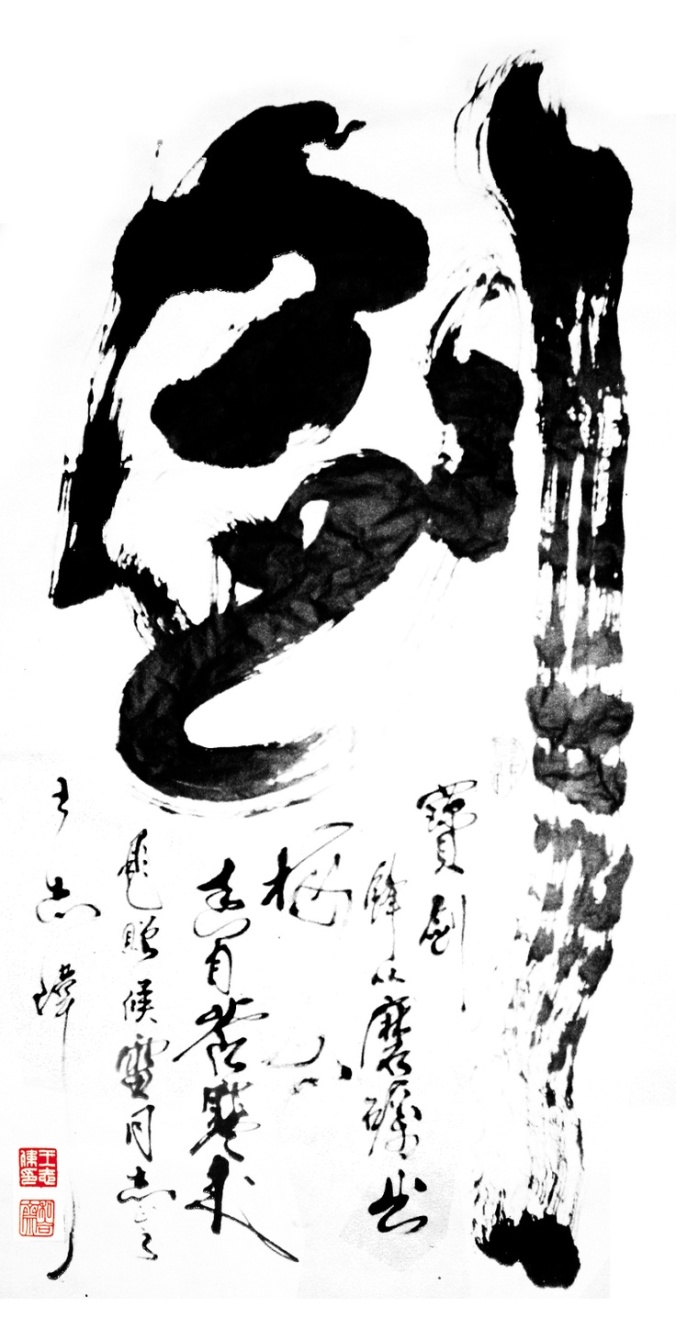

Portrait of General Qi Jiguang

General Qi Jiguang (戚繼光, Qījìguāng; 1528 to 1588) is remembered as a hero in Chinese culture. He was an accomplished military commander, who defended his nation repeatedly against foreign invaders. He was also an accomplished martial artist, whose innovative tactics and writings are of critical importance today in understanding the historical context of classical Chinese martial methods.

Qi is most often remembered as one of the key leaders in the campaigns against the devastating pirate raids going on during his lifetime. To combat this threat he completely overhauled the way the soldiers under his command were trained and deployed. Qi was highly critical and outspoken regarding martial arts practice in general during his day, as well as many of the common military tactics and training in use by the army at the time.

Qi Jiguang received his first post as military commander at the age of 17, after the death of his father. He was later sent to take the Imperial examinations in the capital city of Beijing at the age of 22.

The regular Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) military was in shambles during the later years of the Dynasty. By the mid-16th century, the Imperial Army was significantly undermanned and poorly organized for a professional military fighting force. The situation was so bad that in 1550 a Mongol Prince was able to freely loot the suburbs of the capital city. During this siege of Beijing, all the martial artists and military officers in the city, there for the Imperial exams, were recruited for defense. It was during this battle Qi was recognized by commanders, and even the Emperor, as being a capable and courageous potential military talent.

In 1553 Qi was given his first major military post. It was during this time he began to understand the condition of the Ming Dynasty military. The troops were poorly funded and lacked training and the required military discipline. Additionally, many of the military fortifications were in disrepair due to neglect. He would have to make changes if he was to achieve the mission he had been given of combating the growing pirate threat.

These groups of pirates were collectively called Wōkòu (倭寇). This name literally means “dwarf pirates” and was meant to be a slur against the Japanese, who were believed to constitute the majority of their ranks. These groups of pirates and mercenaries routinely raided the Korean and Chinese coasts for centuries, reaching an apex during the 16th century. Although they are often called “Japanese pirates,” in reality these pirate groups were made up not only of Japanese but ethnic Koreans and Chinese as well. There were even known to have been some Portuguese among their ranks. Men from all manner of marginalized groups during these centuries of political and military upheaval and famine became part of these various Wokou operations.

Even among those merchants and sailors attempting to engage in legal commerce, trade with foreigners was illegal in most instances. This closed down a major potential avenue of business for many Chinese merchants in the coastal regions. As a result, many of those engaging in illegal operations believed they had been forced into piracy to make a living or had been made outlaws after being caught by Ming naval forces engaging in illicit commerce. A large number of people were also forced into piracy (essentially slavery) at the point of a weapon by Wokou gang leaders.

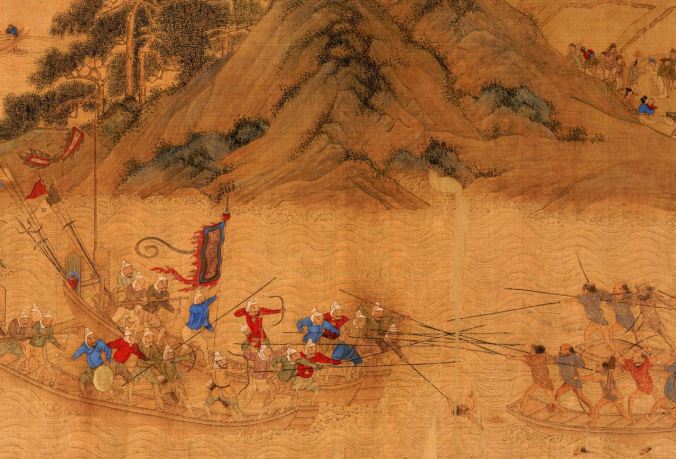

Ming Dynasty painting of a pirate battle.

While the Wokou pirate raids went on for centuries, they were particularly brutal during the reign of the Jiajing Emperor (lived 1507-1567; reigned 1521-1567) in the Ming Dynasty. The Ming had started out strong, taking power after ousting the Mongol Yuan Dynasty (1279–1368). However, after the first couple of generations of experienced Ming military leaders passed away, the Dynasty’s military establishment began to atrophy and rot from the inside. Eventually, it became weak and essentially ineffective.

During this time much of the military was made up of local militias (non-professional soldiers) and a hereditary system of military commanders. General Qi was instrumental in promoting a full-time, paid, professional fighting force. To take on the threat of aggressive piracy with which he had been tasked, Qi Jiguang had to recruit and train new units from within the local militias. To do this he supported the standardization of tactics and equipment, eventually even writing a manual on military efficiency. He needed units that were able to fight the Japanese swordsmen and were fast enough to intercept the pirates as they raided.

These pirate gangs raided and utilized an irregular method of warfare, and the Japanese-style swordsmen in the pirate ranks were well-practiced in their swordcraft. The slow response and tactics of the regular Ming government military proved to be ineffective against the pirate’s methods. Originally Qi was granted only 3000 men to combat the pirates, however, eventually, the numbers were increased dramatically once his methods proved effective.

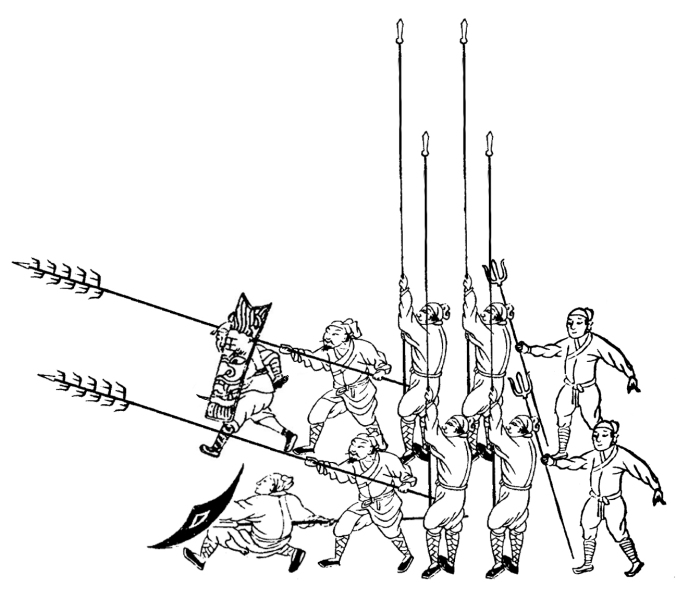

Eventually, he was allowed to institute training and recruitment protocols. He devised a tactic to use spears, polearms and rudimentary firearms to stay out of the range of the pirates fencing methods, called the Mandarin Duck Squad Formation (鴛鴦陣; yuānyāng zhèn). This method of small unit tactics was highly innovative, and not commonly seen on Chinese battlefields at this time. The use of this particular unit formation and tactic required soldiers to aggressively close distance with their opponents and quickly take them out. The General required his soldiers to be in top physical condition and trained them in a strict regimen of martial arts. General Qi believed in using the most straightforward, simple and effective methods, writing “pretty is not practical and practical is not pretty,”

Basic Mandarin Duck formation

His response to the pirates, rather than engage in a direct sword battle, was to utilize better training of his own men, and the use of long weapons. The standard Japanese sword was held with two hands and was longer than the standard Chinese saber, which was utilized with one hand. General Qi Jiguang also trained his soldiers in empty-hand martial arts. He certainly understood unarmed methods were not useful for warfare, however, he insisted empty-hand combative training was useful for developing toughness and courage in his fighters.

It should be noted that the Wokou were not exclusively swordsmen. They used bows and long spears extensively, like most other fighting forces. Qi Ji Guang himself wrote in one of his military treatises, the “Practical Arrangement of Military Training” (練兵實紀, Liànbīng shí jì), “Government troops use only long shields and short sabers, while Wokou use long spears and heavy arrows.” It had been observed that the outdated and undisciplined regular Chinese Ming forces, and their strategies, had performed especially poorly in close range combat with Wokou fighters. The Wokou, however, hardly had any cavalry capability, which would have been impractical for their type of amphibious quick raids.

His new training methodologies were first put to the test in 1559, with their first battle against pirate activities. While this was successful, it is important to remember that the pirates were not one centrally controlled group, but rather many elusive groups spread through the entire coastal regions of China, Japan and Korea. The campaigns against the pirates were protracted, and certainly not without losses.

This military campaign is also famous in Shaolin martial arts history due to the enlistment of monastic soldiers by the government, from Shaolin as well as from the other monasteries. Monastic soldiers are well documented to have participated in four known battles, including one where 120 monastic fighters killed over 100 pirates while sustaining only for casualties themselves. The monks in this unit probably came from more than one monastery, however, its commander, Tianyuan, was from Shaolin. It is worthy of note that he earned this position by defeating eight other monastic warriors in both empty hand and weapon combat.

The final major campaign against these pirates is considered to have taken place in the fall of 1565, in the battle on Nan’ao island, just off the coast of southern China, roughly even with the southern tip of Taiwan. Qi Jiguang was one of the major commanders, along with his longtime friend and colleague, General Yu Dayou (1503–1579) who was also famous for being an accomplished martial artist and military commander. After a few smaller “cleanup” campaigns, the Wokou threat was considered stamped out by 1567.

Qi Jiguang’s Mandarin Duck Formation played an important role in these operations against the pirate forces. The basic Mandarin Duck squad was made up of two teams of five soldiers and a squad leader. These two teams paired together are the source of the name “mandarin duck”, as these birds are often seen in pairs. Each team had one swordsman who acted as that team’s leader, one fighter wielding the “Wolf Brush” (狼筅, Láng xiǎn; a long spear with many branch-like arms), two wielding long spears and one with a trident-type weapon called Tǎng bǎ (钂鈀).

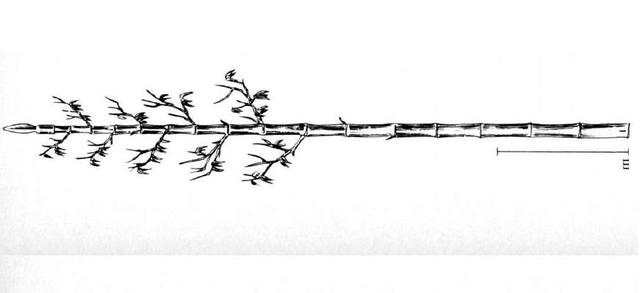

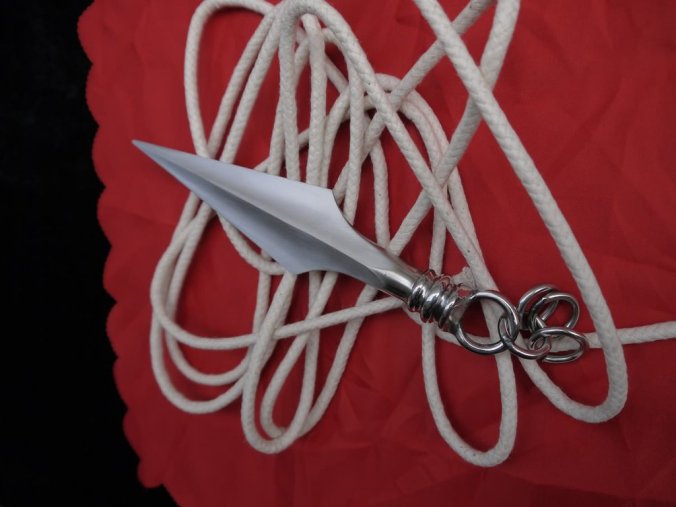

Wolf Brush / Lang xian

Tang pa

The Wolf Brush is certainly an interesting weapon and essentially acted as a mobile wire obstacle. While it was clearly an effective counter to Japanese sword, it wasn’t specifically designed for this role and had existed before General Qi’s inclusion in his new squad formation. It had been effective against pretty much every cold weapon by virtue of being a defensive weapon.

Of the Lang Xian, Wú Shū (吴殳; a.k.a. Wu Yan; 1611 to 1695), a historian, martial artist and martial scholar who lived in the closing days of the Ming dynasty and into the early succeeding Qing Dynasty, wrote in his book the “Army Record” (手臂錄, Shǒubì lù): “The Lang Xian has thirteen layers of branches that can defend against arrow, defend against horse, defend against rolling saber, and defend against long spear. (It is) the best of weapons. However (it is) heavy and cannot kill, which is its disadvantage.”

When confronting enemy forces, the swordsmen (one with a circular rattan shield, and one with a larger tower shield) crouched at the front rank to protect all those behind them with their shields. Once the squad engaged in first contact with the enemy, the swordsman with the circular rattan shield could throw a javelin and make a fast charge toward the enemy. The swordsman with the larger shield (Āi pái, 挨牌) would function as a protective cover. The Lang Xian were projected over the heads of the swordsman and the spearmen guarded the left and right flanks of the Lang Xian. If the enemy managed to get past the Lang Xian and spearmen they had to face the shorter but no less deadly Tang ba.

The Mandarin Duck Formation was also very versatile and adaptable. A rigid, large army structure functioned poorly in the treacherous wetland regions found throughout much of Southern China. The regular Ming army found this out the difficult way. The Mandarin Duck Formation filled the need for a military unit able to change formation at a moment’s notice. It was capable of functioning on a small scale when only a small force was required. It could easily be further divided by the squad leader into smaller units if terrain or circumstances made it necessary. However, it worked equally well in a large-scale battle where many squads could be deployed together.

After successfully suppressing the pirate problem, Qi was put in charge of training for the elite Imperial Guards. Later still he was tasked with repairing sections of the Great Wall and beefing up the Ming’s defensive capabilities against the northern invaders.

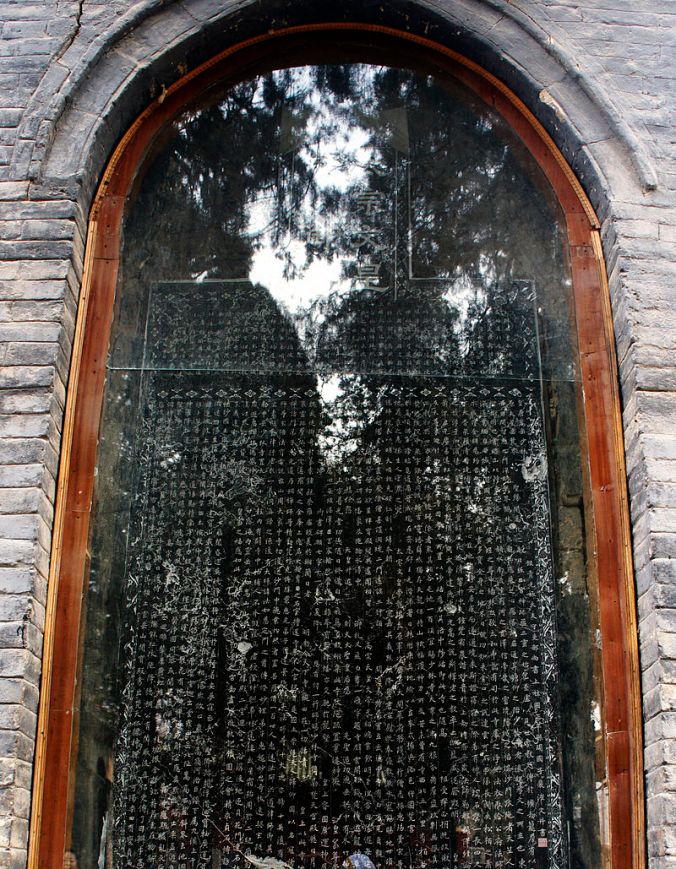

During the 1570s, he engaged in many battles with potential Mongol invaders, keeping this threat to Ming rule at bay. During this period he also wrote the text New Book on Military Efficiency (Jì xiào xīnshū; 紀效新書), on military matters and martial arts. This book was considered an important military reference material for Ming commanders from that time on.

In his later years, Qi’s political power and influence began to wane. Most of his friends and patrons had died, and he became the victim of the political maneuverings of corrupt court officials. In 1583 he was removed from duty. He lived out the rest of his life in poor health and in the poverty of semi-exile, dying early in the winter of 1588. Today, General Qi’s writing is an invaluable source for the historical study of Chinese martial and military arts.

Below are links to two Chinese videos demonstrating the unique small squad formation and strategy General Qi designed for use against the Pirates. Each soldier in the squad would have been well drilled by Qi and his commanders in the use of these martial techniques. This formation was specifically designed to cut through the ranks of Wokou swordsmen.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rd9FMGG9Mp0

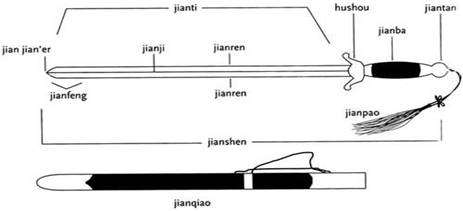

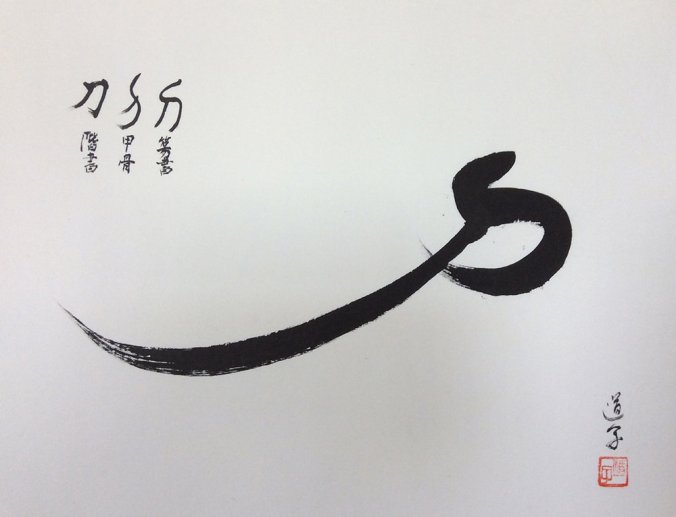

The Chinese characters

The Chinese characters

The hook swords are an interesting construction variant upon the short weapons found in classical martial arts training. Its methods are a combination of techniques of sword/saber (the long, straight sharpened section), cane or hook (the hooked section, which was also sharp), and dagger (which extends down past the handle. The Crescent Moon guard over the grip would be used for blocking, trapping, and striking. Being in the short weapons family, the hook sword can be seen to share about 70-80% of its basic techniques and strategies with other sword/saber methods, with the remainder arising from the unique qualities of its construction.

The hook swords are an interesting construction variant upon the short weapons found in classical martial arts training. Its methods are a combination of techniques of sword/saber (the long, straight sharpened section), cane or hook (the hooked section, which was also sharp), and dagger (which extends down past the handle. The Crescent Moon guard over the grip would be used for blocking, trapping, and striking. Being in the short weapons family, the hook sword can be seen to share about 70-80% of its basic techniques and strategies with other sword/saber methods, with the remainder arising from the unique qualities of its construction.

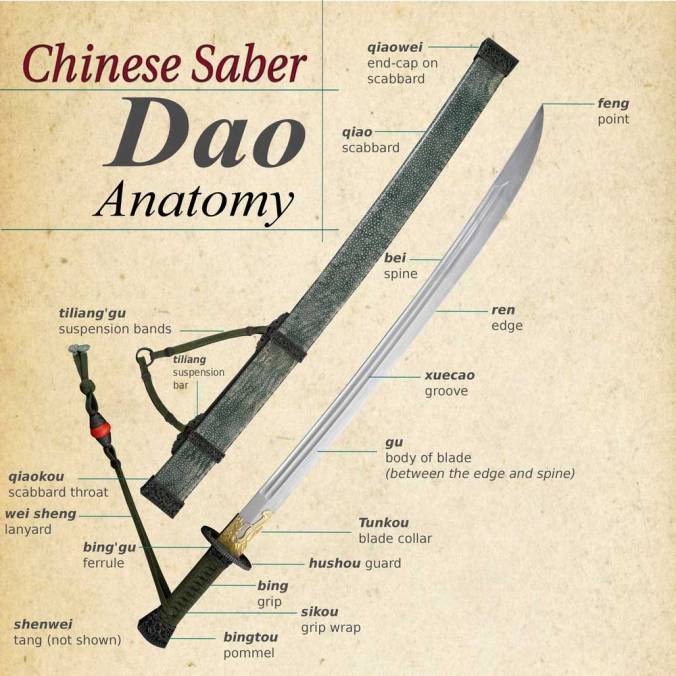

Single saber is a basic Shaolin weapons practice. The saber has many styles and routines. Different saber sets can have very different characteristics and patterns of movement. The single saber is characterized by quick, powerful movements. There are also often many repetitive movements. The predominant techniques are hacking or slashing and thrusting. This style commonly employs strikes as blocks and blocks as strikes.

Single saber is a basic Shaolin weapons practice. The saber has many styles and routines. Different saber sets can have very different characteristics and patterns of movement. The single saber is characterized by quick, powerful movements. There are also often many repetitive movements. The predominant techniques are hacking or slashing and thrusting. This style commonly employs strikes as blocks and blocks as strikes.

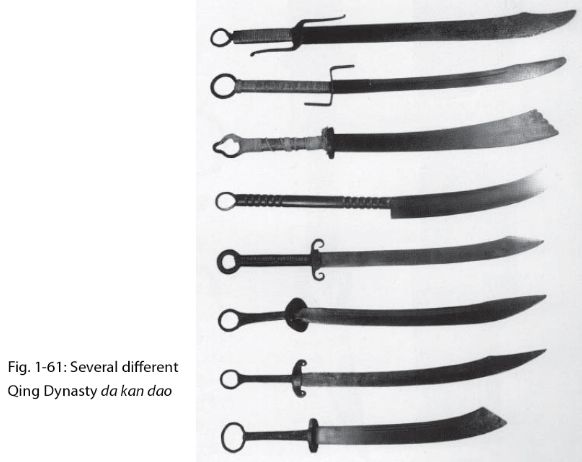

The weapons used by traditional gongfu masters originate mainly from ancient military weapons. The

The weapons used by traditional gongfu masters originate mainly from ancient military weapons. The

During the Tang and Song Dynasties (from the 900s to late 1300s) weapons fighting was the basis of Chinese military arts training. These skills took form and were perfected during this time. Empty-handed fighting remained rudimentary by comparison during this period.

During the Tang and Song Dynasties (from the 900s to late 1300s) weapons fighting was the basis of Chinese military arts training. These skills took form and were perfected during this time. Empty-handed fighting remained rudimentary by comparison during this period. When martial arts existed as battlefield and war arts, weapons were always used. A soldier had to be trained in the use of their primary, as well as backup, battle weapons and empty-handed fighting skills were much less valued because they were not as useful for the battlefield. Just like modern military soldiers, if the ancient warrior got to the point of fighting with their hands, that means they had lost all of their weapons; several things had gone wrong in that engagement.

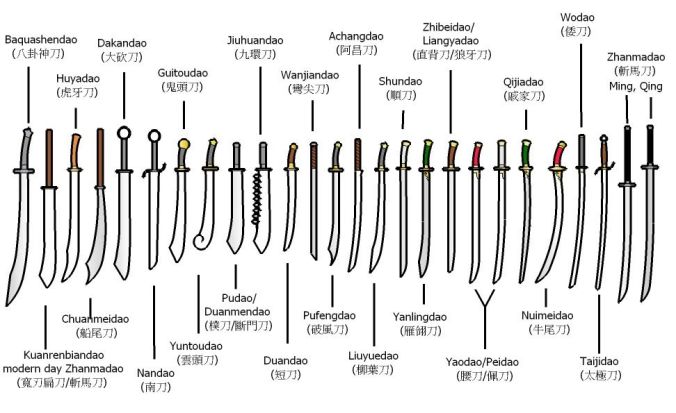

When martial arts existed as battlefield and war arts, weapons were always used. A soldier had to be trained in the use of their primary, as well as backup, battle weapons and empty-handed fighting skills were much less valued because they were not as useful for the battlefield. Just like modern military soldiers, if the ancient warrior got to the point of fighting with their hands, that means they had lost all of their weapons; several things had gone wrong in that engagement. Chinese martial arts weapons training is built around the four primary weapons (staff, saber, spear, and sword). Many systems have many weapons sets, and traditionally there are considered 18 major classifications of weapons. However, a student’s basic weapons education would encompass these four basic constructions, and their techniques can be adapted to all similarly constructed weapons. One would also have some idea of what to expect from an opponent’s weapon style. Familiarity with several types of weapons gave a fighter a better understanding of how an opponent might utilize a weapon should they use one that is similar. Similar weapons will have similar techniques, and just as there are only so many ways to punch and kick, there are only so many ways to swing and thrust a weapon.

Chinese martial arts weapons training is built around the four primary weapons (staff, saber, spear, and sword). Many systems have many weapons sets, and traditionally there are considered 18 major classifications of weapons. However, a student’s basic weapons education would encompass these four basic constructions, and their techniques can be adapted to all similarly constructed weapons. One would also have some idea of what to expect from an opponent’s weapon style. Familiarity with several types of weapons gave a fighter a better understanding of how an opponent might utilize a weapon should they use one that is similar. Similar weapons will have similar techniques, and just as there are only so many ways to punch and kick, there are only so many ways to swing and thrust a weapon.