The Shaolin Monastery is the most famous temple in China, renown for its kung fu fighting monks. With amazing feats of strength, flexibility, and pain-endurance, the Shaolin monks have created a world-wide reputation as the ultimate Buddhist warriors. Yet Buddhism is generally considered to be a peaceful religion, with emphasis on principles such as non-violence, vegetarianism and even self-sacrifice to avoid harming others. How, then, did the monks of Shaolin Temple become fighters?

The history of Shaolin begins about 1500 years ago, when a stranger arrived in China from lands to the west…

Origin of the Shaolin Temple:

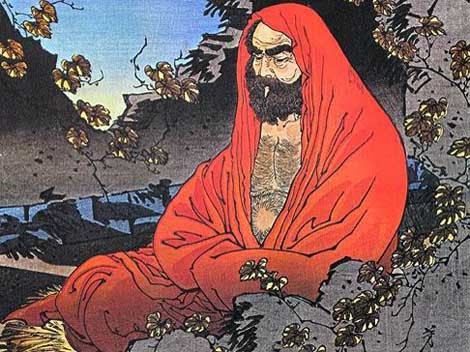

Legend says that c. 480 A.D. a wandering Buddhist teacher came to China from India. He was called Buddhabhadra, also known as Batuo or Fotuo in Chinese. According to later Chan (or in Japanese, Zen) Buddhist tradition, Batuo taught that Buddhism could best be transmitted from master to student, rather than through the study of Buddhist texts.

In 496, the Northern Wei Emperor Xiaowen gave Batuo funds to establish a monastery at holy Mt. Shaoshi in the Song mountain range, 30 miles from the imperial capital of Luoyang. This temple was named Shaolin (Shao from Mt. Shaoshi, lin meaning “grove”).

Early Shaolin History:

Another Buddhist teacher was Bodhidharma, who came from either India or Persia. He famously refused to teach Huike, a Chinese disciple; Huike cut off his own arm to prove his sincerity, and became the Bodhidharma’s first student.

The Bodhidharma also reportedly spent 9 years in silent meditation in a cave above Shaolin. One legend says that he fell asleep after seven years, and cut off his own eyelids so that it could not happen again. The eyelids turned into the first tea bushes when they hit the soil.

In 534, Luoyang and the Wei Dynasty fell. Temples in the area were destroyed, possibly including Shaolin.

Shaolin in the Sui and Early Tang Eras:

Around 600 A.D., Emperor Wendi of the new Sui Dynasty awarded Shaolin a 1,400-acre estate, plus the right to grind grain with a water mill. The emperor was a committed Buddhist himself, but most of his court supported Confucianism instead.

The Sui reunified China, but lasted only 37 years. Soon, the country once more dissolved into the fiefs of competing warlords.

Shaolin Temple’s fortunes rose with the ascension of the Tang Dynasty in 618, formed by a rebel official from the Sui court. Shaolin monks famously fought for Li Shimin against the warlord Wang Shichong. Li would go on to be the second Tang emperor.

Shaolin Temple in the Tang Era:

Despite their assistance to the early Tang rulers, Shaolin and China’s other Buddhist temples faced numerous purges. In 622, Shaolin was shut down and the monks forcibly returned to lay life. Just two years later, the temple was allowed to reopen due to the military service its monks had rendered to the throne. In 625, Li Shimin returned 560 acres to the monastery’s estate.

Relations with the emperors were uneasy throughout the 8th century, but Chan Buddhism blossomed across China. In 728, the monks erected a stele engraved with stories of their military aid to the throne, as a reminder to future emperors.

The Tang to Ming Transition:

In 841, the Tang Emperor Wuzong feared the power of the Buddhists, so he razed almost all of the temples in his empire and had the monks defrocked or even killed. Wuzong idolized his ancestor Li Shimin, however, so he spared Shaolin.

In 907, the Tang Dynasty fell, and the chaotic 5 Dynasties and 10 Kingdom periods ensued. The Song family eventually prevailed, ruling until 1279. Few records of Shaolin’s fate during this period survive. We know that in 1125, a shrine was built to Bodhidharma, 1/2 mile from Shaolin.

The Song was followed by the Mongol Yuan Dynasty, which ruled until 1368.

Shaolin’s Golden Age:

As the Yuan Dynasty crumbled, Shaolin was destroyed once more during the 1351 Hongjin (Red Turban) rebellion. Legend states that a Bodhisattva, disguised as a kitchen worker, saved the temple; in fact it was burned to the ground.

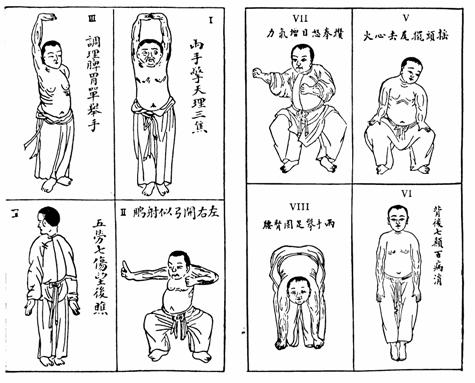

Still, by the 1500s, the monks of Shaolin were famous for their staff-fighting skills. In 1511, 70 monks died fighting bandit armies. Between 1553 and 1555, the monks were mobilized to fight in at least four battles against Japanese pirates.

The next century saw the development of Shaolin’s empty-hand fighting methods. However, the monks fought on the Ming side in the 1630s – and lost.

Shaolin in the Early Modern Era:

In 1641, rebel leader Li Zicheng destroyed the monastic army, sacked Shaolin and killed or drove away the monks. He went on to take Beijing in 1644, ending the Ming Dynasty, but was driven out in turn by the Manchus who founded the Qing Dynasty.

Shaolin Temple lay mostly deserted for decades. The last abbot, Yongyu, left without naming a successor in 1664.

Legend says that a group of Shaolin monks rescued the Kangxi Emperor from nomads in 1674. According to the story, envious officials then burned down the temple, killing most of the monks.

Gu Yanwu traveled to the remains of Shaolin in 1679 to record its history.

Shaolin in the Qing Era:

Shaolin slowly recovered from being sacked; in 1704, the Kangxi Emperor made a gift of his own calligraphy to signal the temple’s return to imperial favor. The monks had learned caution, however, and empty-hand fighting began to displace weapons training. It was best not to seem too threatening to the throne.

In 1735-6, the emperor Yongzheng and his son Qianlong decided to renovate Shaolin and cleanse its grounds of “fake monks” – martial artists who affected monks robes without being ordained. The Qianlong Emperor even visited Shaolin in 1750, and wrote poetry about its beauty, but later banned monastic martial arts.

Shaolin in the Modern Era:

During the nineteenth century, the monks of Shaolin were accused of violating their monastic vows by eating meat, drinking alcohol and even hiring prostitutes. Many saw vegetarianism as impractical for warriors; this is probably why government officials sought to impose it upon Shaolin’s fighting monks.

The temple’s reputation received a serious blow during the Boxer Rebellion of 1900, when Shaolin monks were implicated (probably incorrectly) in teaching the Boxers martial arts.

In 1912, China’s last imperial dynasty, the Qing, fell due to its weak position compared with intrusive European powers. The country fell into chaos again, which ended only with the victory of the Communists under Mao Zedong in 1949.

Meanwhile, in 1928, the warlord Shi Yousan burned down 90% of the Shaolin Temple. Much of it would not be rebuilt for 60 to 80 years.

Shaolin under Communist Rule:

At first, Mao’s government did not bother with what was left of Shaolin. However, in accordance with Marxist doctrine, the new government was officially atheist. In 1966, the Cultural Revolution broke out, and Buddhist temples were one of the Red Guards’ primary targets. The few remaining Shaolin monks were flogged through the streets and then jailed; Shaolin’s texts, paintings, and other treasures stolen or destroyed.

This might have finally been the end of Shaolin, if not for the 1982 film Shaolin Shi or “Shaolin Temple,” featuring the debut of Jet Li (Li Lianjie). The movie was based very loosely on the story of the monks’ aid to Li Shimin, and became a huge smash hit in China.

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, tourism exploded at Shaolin, reaching more than 1 million people per year by the end of the 1990s. Shaolin’s monks are now among the best known on Earth; they put on martial arts displays in world capitals, and literally thousands of films have been made about their exploits.

Batuo’s Legacy

It’s hard to imagine what the first abbot of Shaolin would think if he could see the temple now. He might be surprised and even dismayed by the amount of bloodshed in the temple’s history. However, to survive the tumult that has characterized so many periods of Chinese history, the monks of Shaolin had to learn the skills of warriors. Despite a number of attempts to erase the temple, it survives and even thrives today, there at the base of the Songshan Range.